| News & Events |

| Location:Home > News & Events > Science and Technology News |

| What Did George Washington Really Look Like? |

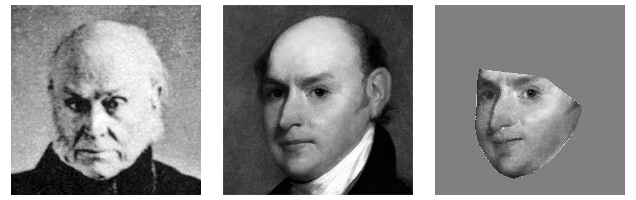

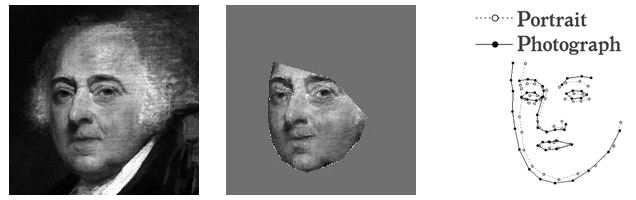

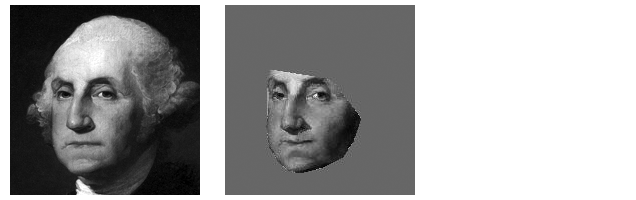

From the dollar bill to the walls of esteemed museums, portraits of George Washington are everywhere. But all of these images share the same flaw: They don't tell us what the man really looked like. Now, thanks to some clever sleuthing and a bit of computer processing, researchers say they have uncovered the true face of the first president of the United States—and of a handful of other famous people.  Small changes. An 1843 photo of John Quincy Adams, an 1818 portrait by Gilbert Stuart, and a reconstructed "photograph" using the researchers' algorithm. Credit: Courtesy of Eric L. Altschuler Physician and history enthusiast Eric Altschuler of the New Jersey Medical School in Newark was walking through the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., when he hit upon a clever idea. The museum houses many of the works of the early 19th century painter Gilbert Stuart, whose portraits of the founding fathers, the first six American presidents, and other famous individuals hang from the walls. Altschuler noticed that a few of the people that Stuart painted—President John Quincy Adams and Senator Daniel Webster, for instance—were alive in the early days of the camera; photographs and portraits of them exist. Could these photographic "Rosetta Stones" uncover the true visage of Stuart's early subjects?  The artist's signature. In outlines (right) made of the faces in a photograph (left) and a portrait (center) of Senator Daniel Webster, Stuart's artistic license becomes clear. Credit: Courtesy of Eric L. Altschuler With the help of graduate student Krista Ehinger of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Altschuler spent months on the Internet tracking down six photographs of people Stuart had also painted, including Webster, Quincy Adams, John Collins Warren, and Josiah Quincy. The researchers drew computer outlines of the faces in the portraits and in the photos, measuring the differences between the two. That gave them a sense of how Stuart's artistic style differed from reality. Fuller cheeks and higher eyebrows, for example, tend to mark a Stuart portrait. The duo then created a computer algorithm that took an average of the portrait and the painting. They applied the method to portraits of the presidents who lived before photography, effectively subtracting Stuart's signature changes.  Time travel. By applying the face-mapping technique (right) to a portrait of John Adams (left), the researchers reconstructed a "photograph" of the second president. Credit: Courtesy of Eric L. Altschuler The technique, described online this month in Perception, revealed only subtle differences between the portraits and the retroactive "photographs," and it's tough to draw any major conclusions with so few photograph-portrait pairs to work with, say the authors. Right now, the differences are "hard to get excited about," says neurobiologist Margaret Livingstone of Harvard Medical School in Boston, who was not involved with the study. "Stuart's a good painter; the portraits are probably what they looked like," she says. "The differences are minor compared to the effects of aging in photographs taken decades later."  True visage. George Washington couldn't tell a lie, but his portrait might fib a bit. Here's what he may have really looked like. Credit: Courtesy of Eric L. Altschuler But as more examples are found, Stuart's method will become clearer, and some more major alterations he made may emerge in a refined model, says Ehinger. "It'd be awesome if the great-great-great-grandchildren of some of these people had photographs sitting around in their attics," she says. The researchers have set up a Web site where descendants can submit these keepsakes. In the meantime, Altschuler is hoping to find more photograph-portrait pairs of lesser-known individuals from the early 1800s. He's now looking at painting-photograph pairs of the subjects of Thomas Lawrence, president of 'the U.K. Royal Academy of Arts and painter of European nobility in the early 1800s. "As other examples are found, we can go back and test them against our model," Altschuler says. The researchers are also continuing to refine their method to include the color and texture of the face as well as its shape. by Sara Reardon on |

| Appendix Download |

|

|